Critical minerals are a moveable feast it seems. Initially understood to mean decarbonising battery electric vehicle minerals such as lithium, the critical minerals family is now a thing to be defined by the strengths and anxieties of any who care to expound on the matter. So in South Africa, coal makes the list, the mineral least suitable for decarbonisation.

Iron ore hasn’t generally commanded attention in the critical minerals discussion. Mined to supply steel manufacturers, the mineral is generally perceived in terms of a carbon present the world wants to escape. That all changes, however, if iron ore can be processed with carbon credits.

This is the niche Zanaga Iron Ore Company (ZIOC), a London-listed company, wants to occupy. For more than a decade, the Zanaga iron ore prospect in the Republic of Congo (RoC) was ignored until in April when ZIOC’s 43% shareholder Glencore was bought out.

The buyer is a consortium led by ex-Anglo CEOs Mark Cutifani and Tony Trahar, as well as former Xstrata boss Mick Davis. Along with other investors they raised $23m via a share issue. Once Glencore was bought out ZIOC well and truly set Zanaga on a path of re-evaluation. If they succeed, the project could become a high-value, low-cost 30 million tons a year iron ore supplier.

The question is what makes Zanaga fly now when Glencore’s feasibility study in 2013 found it to be uneconomic? And to give present context to this question, it’s worth acknowledging that the iron ore market has weakened during the past two to three years.

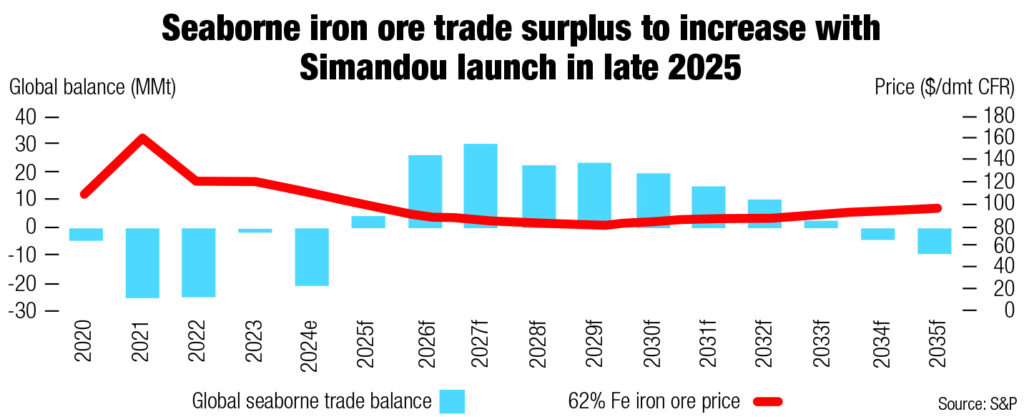

“Investors are generally indifferent towards iron ore,” said UBS in June. The bear case in the mineral had not “played out” over the past five years while supply is expected to increase, it added. A consortium involving Rio Tinto is commissioning the giant $11.6bn Simandou project in Guinea, for instance. It will add 60mt a year of the material in its first year, doubling thereafter.

According to S&P Global Metals, a credit ratings company, Simandou will contribute towards a 20mt to 30mt supply surplus in 2026 and 2027. This comes as short-term steel production declines in China, the single-largest buyer of the mineral.

Commenting in its non-ferrous metals briefing in June, S&P said it expected Chinese steel production to drop 40mt this year owing to “mill economics and profitability, rather than enforced production cuts”.

Said Goldman Sachs in a recent report: “While policy rhetoric around capacity cuts has lifted sentiment, structural overcapacity in China’s steel industry remains unresolved, and enforcement of meaningful production curbs is unlikely amid macroeconomic pressures.”

However, ZIOC’s backers say there have been three major shifts in the iron ore market since 2013.

The first is the project’s flow sheet has been modernised to accommodate technology capable of extracting higher grade iron ore with fewer impurities. Secondly, grades of iron content in established iron ore supply, such as Australia’s Pilbara basin, are on the decline which opens up an opportunity for a high-grade operator.

The iron content of Australian production is now a little over 60% iron compared to ZIOC’s direct reduction iron technology which is forecast to yield 68.5% iron in the project’s first 12mt per year first stage, says Andrew Trahar, head of corporate development at ZIOC.

The third factor is climate change.

Steelmakers are increasingly preferring low carbon supply from electric arc furnaces. This technology emits less carbon than coke-burning blast furnaces to which lower quality iron ore is supplied. This could be ZIOC’s most competitive feature, adds Trahar.

“Electric arc furnaces are lower capital intensity, lower operating cost, more efficient, and cleaner. But you have to have the right kind of feedstock to supply them. In the past 10 years, people have been actively progressing their electric arc furnace strategies, particularly Japan, the Middle East, and even in the US, where approximately 80% of current production of steel in the US is electric arc furnace.”

A second-stage expansion of Zanaga of 18mt/y will yield better-yet iron ore and take the project’s total capital outlay to $2.2bn. This is less capital intensity than other iron ore projects, but with price premium baked in, hopefully, says Trahar.

“If we can produce this high-grade product at similar capital and operating costs, we will be producing a product that today sells for about $130/t, whereas the benchmark product that we were being based off previously is a 65% pellet feed blast furnace product that was trading at $115/t. So the current spot price for this kind of product is about $15/t above our previous type of product,” he says.

As for next steps, Trahar says ZIOC is funded for at least the next 12 months while it builds and communicates its investment case about the project. Bulk sampling is another important milestone. Essentially, the project has a bankable study it has updated.

The big question after that is how to finance the capital. Options include a partial sell-down of shares by the consortium. Offtake with a project builder is another. “There are so many different ways in which you can cut the cake here, and we’re going to have to run this process down with our strategic partners before we can actually reach a final conclusion,” says Trahar.

It’s also worth noting the project’s backers are private equity and will be mindful of an exit. “We’re value-driven,” says Trahar. “As a company, we have to be focused on value rather than the emotion of chasing operational status for the project.”