South Africa has the critical minerals that the US needs to industrialise, including rare earth minerals, President Cyril Ramaphosa told President Donald Trump in their meeting in May.

But having the deposits is only the beginning. It takes a lot more to make those deposits investible.

Critical minerals are those that are essential for modern technology, from computers to aerospace, renewable energy and transport. Each country has its own list: South Africa ranks platinum, manganese, iron ore, chrome ore and, controversially, coal as the most critical in its recently released Critical Minerals and Metals Strategy. The US-based Critical Minerals Institute has a list of 21, including PGMs and manganese but also copper, cobalt, lithium, nickel and rare earth elements (REEs).

REEs have been a particular focus of the US because China dominates both mining and midstream processing, which gives it enormous power. “I think every geologist is looking at critical minerals at the moment,” junior mining entrepreneur Errol Smart says. “South Africa possesses deposits, but there has been a dearth of exploration into them. We have very interesting rare earth potential, but it takes time to develop these deposits and it all comes back to permitting and licensing and shipment.”

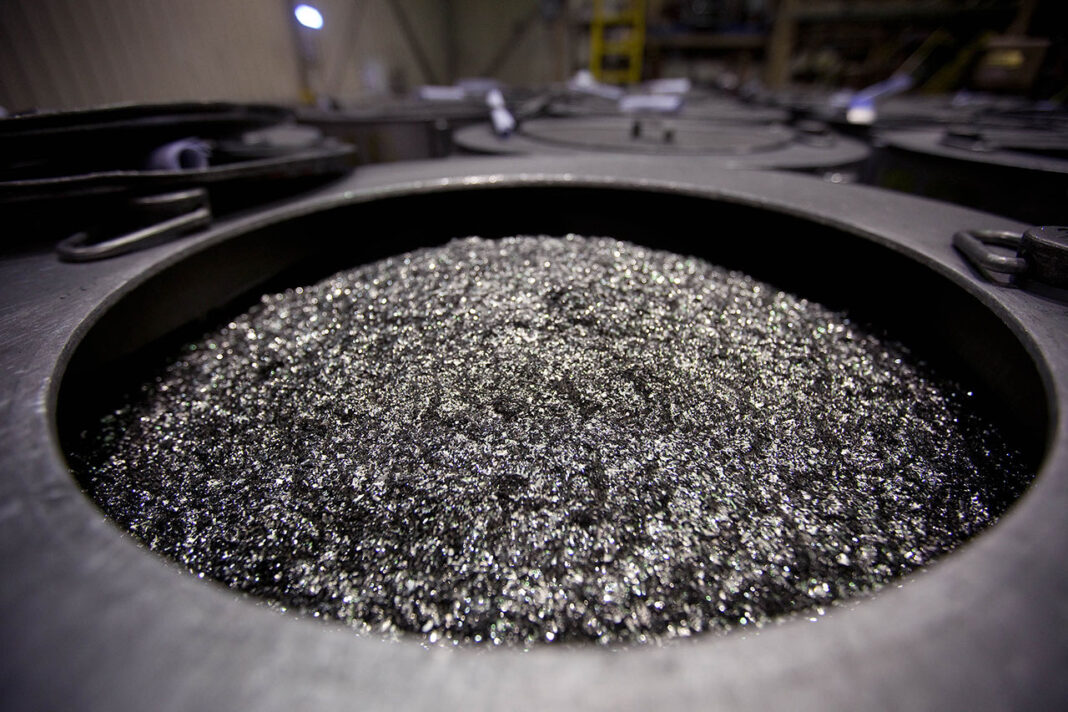

Rainbow Rare Earths has proven that it is possible to extract magnet REEs from phosphogypsum contained in dumps at Phalaborwa by producing a mixed rare earth carbonate at its plant at Mintek. Rainbow CEO George Bennett said REEs were not particularly rare. However, it was rare to find an economically robust project, because these minerals are expensive to bring into production and prices are kept artificially low by the Chinese. Rainbow has an advantage in that it is planning to exploit a surface deposit that has already been chemically cracked, enabling it to produce separated rare earth oxides (REOs) at relatively low cost.

Rainbow has indirect US government backing through its minority shareholder TechMet. It also has direct backing from the US in the form of a funding proposal from the US Development Finance Corporation to invest $50m into Phalaborwa’s development at the project level.

“As a business, you have to look at what the rest of the world needs,” Smart said.

“The US might facilitate funding for minerals that it needs – it has already shown with its investments in the Lobito Corridor and the Democratic Republic of the Congo that it is willing to do so – but when you have government involvement, the issues can go beyond simply economic.”

South Africa has two other known REE projects: Zandkopsdrift, which is being developed by Frontier Rare Earths and has been selected by the European Union as one of 13 strategic raw material projects; and the Steenkampskraal Monazite Mine, owned by Steenkampskraal Holdings, Bora Mining Investments and the Enock Mathebula Foundation.

South Africa’s Critical Minerals Strategy proposes a number of measures to accelerate development of its specified minerals, with a particular emphasis on local beneficiation.

To encourage exploration, it proposes addressing regulatory bottlenecks and streamlining licence applications with a one-shop system, adding to the Junior Mining Exploration Fund and considering the adoption of a flow-through shares scheme. Financial incentives should include differentiated electricity tariffs, R&D tax credits, special economic zones and beneficiation hubs that offer tax benefits.

“Preferential power pricing would be welcome, as power is our second-biggest operating cost. We would also welcome fiscal incentives,” Bennett said. But he added that moving from primary to midstream production would not be in SA’s interests. Making magnets from REOs was highly complex and the midstream was not particularly profitable. Although these magnets are used by the automotive industry, South African car manufacturers are already sourcing them from China.

Minerals Council South Africa chief economist Hugo Pienaar said the council gave input into the list of South Africa’s critical minerals, but did not help to draft the strategy document.

“There is a lot we would support in the strategy, such as corporate tax relief, industrial development zones and preferential power pricing,” Pienaar said. “But what is seemingly lacking is the buy-in from all the stakeholders that would have to make it work. For example, National Treasury would have to approve sectoral incentives and, outside the vehicle sector, has not been supportive of this in the past.

“While we support the emphasis on beneficiation, South Africa also needs to support primary extraction. To the extent that it makes commercial sense to do value addition, we should create a favourable environment for it.”