Mark Bristow describes the impasse with Mali’s government over its allegations of unpaid taxes as the most stressful situation he’s had to manage. That’s saying something. Bristow’s African mining career spans more than 31 years, starting with Randgold & Exploration in 1994 and culminating in the 2019 merger of Randgold Resources with Barrick Mining Corp, the Canadian firm he intends to run until 2028, when he plans to retire.

At the time of writing, Mali’s military junta, in power since a 2021 coup-within-a-coup, had put the ~700,000 (on a 100% basis) ounce a year Loulo-Gounkoto into administration, effectively taking over its management. This is a cause of major discomfort for Barrick. “There’s no way that we can allow strangers to get access to our SAP platforms and we have since terminated access,” says Bristow.

That’s just one hazard of government’s on-site control of the operation. Another is the mine is potentially endangered operationally. Ironically, the most qualified to operate the mine are the four Malian executives, employed by Barrick, imprisoned by their own government on trumped-up charges. Says Bristow: “They are top-flight engineers and geologists and accountants. While we support them and we talk to them, it’s the most stressful thing I’ve ever managed – a situation like this.”

Right now, Bristow sees no option but to press ahead with international arbitration in order to solve the dispute with Mali, a process he believes will be speedier than many imagine, if that’s the route events take. “It’s the only lever we have,” Bristow says, adding that Barrick remains open to a negotiated agreement.

The dispute with Mali reaches back more than 12 months after the junta enacted a new mining code in terms of which it insisted on a new ownership model, and increased taxes. Barrick has made additional payments to government, but a final agreement is currently out of reach, despite nearing a settlement on three separate occasions, each time rowed back by government.

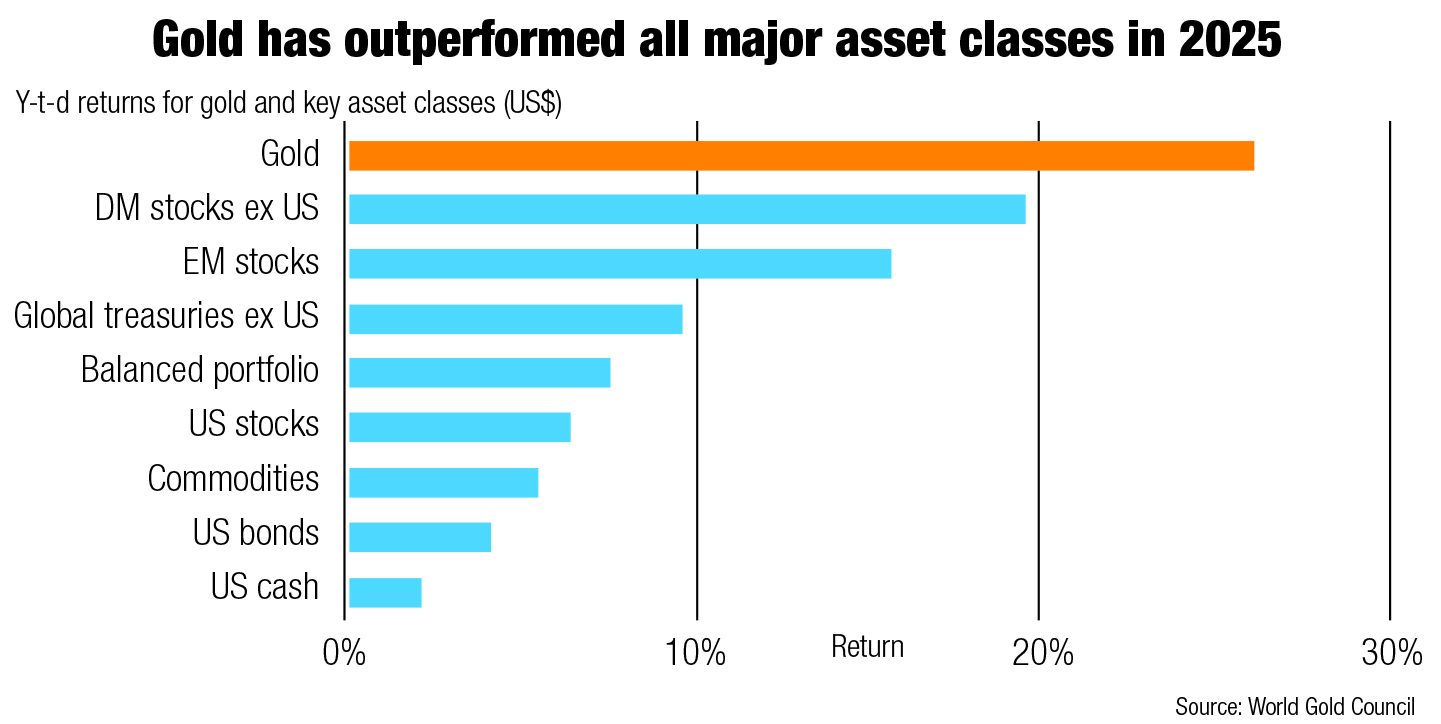

It’s made for a difficult time for Barrick. While shares in the company have benefited from the sky-high gold prices, it has not performed as well as peers. “We like Barrick for its solid asset-base and excellent exploration potential but see this constrained by ‘resource nationalism’ at its Mali asset,” commented Bank of America analysts earlier this year. They also pointed to “difficulties at Pueblo Viejo”, Barrick’s Dominican Republic mine. According to Scotia Bank’s Tanya Jakusconek, Barrick’s production guidance for the 2025 financial year was also slightly disappointing.

Bristow acknowledges there’s been underdelivery in parts of Barrick’s recent operational performance. In a comparison of 12 gold companies, Barrick reported the second-highest all-in sustaining costs in the first quarter. Yet Barrick leads the line in other metrics. Along with US rival Newmont, Barrick spends the most on exploration and evaluation.

The big thing in the gold industry is that optionality, that long life, and I learnt that very quickly – that you need long-life mines

Mark Bristow

Bristow thinks the firm gets no credit in its valuation for its strategy of reserve development. The market, he believes, is rating short-term wins instead of valuing long-term gold reserve growth. This is not a new grumble of Bristow’s, but it’s been given greater weight by the performance of the gold price recently.

Bristow, however, thinks gold reserve development has been ignored, and not just recently. “Since 2015, the gold price has been going up to where it is today. So it’s continually allowing the industry to mine on the margin, which means you’re not really mining long-life reserves. You’re mining the margin built by the gold price, and your sustaining capital is relatively low.

“The big thing in the gold industry is that optionality, that long life, and I learnt that very quickly – that you need long-life mines,” says Bristow. “And the gold industry survives on 10-year life of mine and less. If you look at the gold industry today, there are not many plus-10-year life businesses, gold businesses.”

Barrick has replaced 110 million ounces in gold reserves, which are economic at a $1,400/oz gold price, at an average $10 per ounce. It’s an effort though that comes with risk and high capital.

Breathing fresh life into Reko Diq, a prospect in northern Pakistan, has proved contentious. Barrick has also extended and expanded Lumwana, a large copper mine in Zambia. The two mines are worth 35 years plus in gold equivalent production, Bristow says. Other mines such as Kibali, Nevada Gold Mines (held in joint venture with Newmont), mines in Tanzania as well as Loulo-Gounkoto and Kibali in the Democratic Republic of Congo, have economic reserves worth 15 to 20 years each.

Set against this, co-product adjusted output from the major miners has been on the decline since 2009, down to about 6.6 million oz in the first quarter of this year (see graph). The sight of a diminishing sector has failed to attract new investors into the sector, says Bristow. This is despite what’s been happening with the gold price. “We haven’t attracted the generalist investor, and the investors have become shorter and shorter term,” he says.

What’s critical to note about Bristow is that his philosophy is shaped by his professional schooling in geology. Deposits, formed over millennia, can take more than a generation to find and build – a time perspective at odds with the investment sector’s quarterly roster. So enraged was Bristow during one round of investor calls several years ago that he dubbed critical analysts “quacking ducks”.

Nonetheless, Barrick’s recent cost underperformance, and the zero-sum game adopted by Mali’s junta, has thrown the spotlight on whether Bristow has lost focus. The Financial Times recently reported Barrick’s board had “formalised” the CEO succession process. (Although it’s perhaps also worth acknowledging Barrick chair John Thornton’s comments last year after taking up non-executive duties at the group. “Who needs to be an executive when the CEO is Bristow,” he said).

Bristow is relaxed on the matter. “People are trying to find excuses for the discounts,” he says. “We’ve got to deliver on this build-out [of projects]; we’ve got to deliver on Nevada [Gold Mines], and it’s coming. We stumbled over Mali, but not through anything we did.

“At the end of the day, I’ve been very clear that my plan is to leave at the end of 2028, when the two big projects – Lumwana and Reko Diq – would be in the process of commissioning. And it’s a good time to leave. We’ve told the market that already last year, and we areworking on succession,” he says.

In the meantime, the market appeared to be waking up to Barrick’s strategy, Bristow says. “Analysts are at least starting to recognise our net asset value. That’s a great first step, because we are getting out of that challenging rebuild phase.

“We have been attracting a discount because people feel that I’m putting more capital into growth and I should be paying dividends. That’s not the investor I want to attract. I want to attract owners who are going to come for the ride with us.”