In 1938, a fishing trawler off the coast of South Africa’s Eastern Cape province netted a curious fish that was drawn to the attention of naturalist Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer in East London.

It turned out the fish was a coelacanth. Known from the fossil record, the species was believed to have been extinct for 70 million years. The discovery was regarded at the time as scientific treasure and underscored a wider point: the depth of our ignorance about the depths of the sea.

Almost a century later, Neptune’s realm remains murky despite massive advances in our understanding of the seas. But new fossilised treasures in the form of critical minerals are seen down deep and there is a lot of hype – and alarm – about mining’s newest frontier.

US President Donald Trump threw the subject into sharp relief in April with an executive order entitled ‘Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources’.

“Vast offshore seabed areas hold critical minerals and energy resources. These resources are key to strengthening our economy, securing our energy future, and reducing dependence on foreign suppliers for critical minerals,” the order said.

That raised red flags with the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN body that is supposed to regulate all mineral- related activity on the seabed in international waters that lie beyond the 200-mile (320km) economic zones that countries with coastlines have jurisdiction over.

ISA said that the move “…raises specific concerns because while the order primarily addresses domestic political and policy matters, its reference to applicability in areas beyond national jurisdiction becomes a matter of the rule of law within the global ocean governance framework known as UNCLOS (the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea).”

ISA was also rattled by the subsequent application from the Metals Company USA to extract deep-sea minerals in international waters – bypassing ISA’s authority.

These developments are unfolding against a backdrop of worldwide urgency as the green energy transition – which is not on Trump’s agenda – and older trends such as urbanisation gather pace. The trajectory the global economy is taking is simply not possible without a wide range of metals and minerals, and lots of this stuff is needed to keep the wheels turning.

With warnings of looming metals shortages and uncertainties about the extent of undiscovered, economically viable mineral resources on land, attention is turning to the seabed.

Oceans cover 71% of the surface of the planet we curiously call Earth, and humans have long extracted resources from the sea that go beyond fish and other wildlife.

Much of the oil and gas industry, for example is focused on drilling and wells in deep water, and there is also mining beneath the sea.

The Boulby Mine in North Yorkshire, England, for example, which produces potash, is more than 1,400m deep and its tunnels extend for several kilometres beneath the sea. And off the Atlantic coasts of South Africa and Namibia, diamonds are collected from the bottom of the ocean in relatively shallow waters near the shore.

But deep-sea mining is a completely different kettle of fish. It aims to unlock the wealth from the ocean floor that is contained in potato-sized polymetallic ‘nodules’ as well as sulphides and metal-rich crusts that form on underwater mountains.

The nodules are like nuggets of nickel, copper, cobalt and manganese, while the sulphides contain “large amounts of copper, zinc, lead, iron, silver and gold”, according to ISA. The crusts are rich in cobalt.

“The seabed truly is metal-rich, and for nodules the excavation need reach only the upper decimetre of mud, not kilometres into the crust,” Glen Nwaila, director of the Wits Mining Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, told Miningmx.

“Nevertheless, the leap from a geologically impressive resource to a proven, economically viable reserve depends on closing gaps in spatial sampling, demonstrating that full-scale systems can operate reliably at five-to-six-kilometre water depths, and showing that long-term environmental liabilities, whether plume dispersion, biodiversity loss or costly restoration, can be contained within an acceptable cost envelope.”

Mining projects are costly, but this takes things to new depths.

“Turning these geological resources into mineable reserves is expensive. A single first-generation operation designed to lift three million dry tons of nodules per year is expected to require capital outlays of roughly $1.3-1.8bn for collector vehicles, a riser-lift system, a production-support vessel and a shore-based hydrometallurgical plant,” Nwaila said.

“Recent modelling of post-mining habitat rehabilitation estimates that recreating nodule substrata or stabilising disturbed sediment would cost between $5.3m and $5.7m per square kilometre, roughly double current estimates of extraction cost per square kilometre, so any future regulatory requirement for restoration could alter project economics materially.”

The equipment required also comes with high maintenance costs linked to the depths involved and the direct exposure to salt water which causes rust.

And if cobalt or nickel prices were to flatline or decline, shareholder value would sink like an anchor.

“Financial-risk analyses have warned that, under flat or declining cobalt and nickel price scenarios, deep-sea nodule projects could destroy [from] $30bn to more than $100bn of shareholder value over two decades,” Nwaila said.

And the “acceptable cost envelope” remains shrouded in the mists of the deep.

“Mining on land is difficult enough,” Paul Dunne, the CEO of Northam Platinum, who is also president of the Minerals Council South Africa, noted in a conversation with Miningmx when asked about seabed mining.

Still, this is not science fiction like something out of Jules Verne’s classic 19th-century novel, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. It’s real and capital is being deployed in what may potentially be a new rush to salvage this marine treasure trove.

While no commercial exploitation has been approved to date by ISA for the extraction of marine minerals in the depths – not least because regulations governing deep-sea mining are still under development – it has issued exploration contracts to assess the potential.

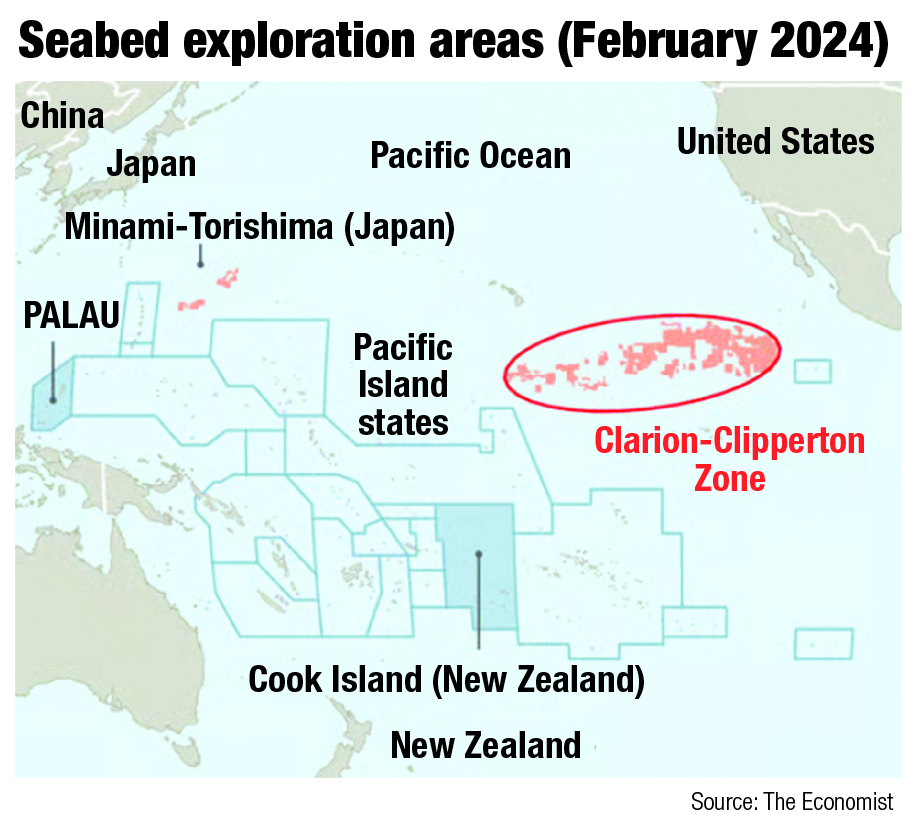

In total, according to its website, ISA issued 30 contracts to 21 contractors sponsored by 20 countries for the exploration of the three types of mineral resources in what it calls “the Area” – the international seabed that covers 54% of the planet’s surface.

The 20 sponsor states pointedly don’t include the US – which is not a signatory to UNCLOS – or any African countries.

“The States sponsoring these contracts (are) Belgium, China, the Cook Islands, France, Germany, India, Japan, Kiribati, the Republic of Korea, Nauru, Poland, the Russian Federation, Singapore, Tonga and the United Kingdom. Bulgaria, Cuba, Czechia, Poland, the Russian Federation and Slovakia also sponsor a contract through the Interoceanmetal Joint Organization,” ISA says.

“The areas explored include the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) (in the Pacific Ocean), the Indian Ocean, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the Northwest Pacific Ocean.”

AFRICA MISSING OUT?

Africa at this point seems to be missing out on most of this scramble, but it has a history in this regard which could point the way to how the future unfolds.

Over a decade ago, applications had been made to explore for seabed minerals in the waters off Madagascar and Mauritius, and some exploration has taken place in South African waters, according to a 2014 policy briefing report by the South African Institute of International Affairs.

Namibia’s waters have also been seen as prospective and scientific studies were conducted there as far back as the 1970s which uncovered significant phosphate deposits at depths of 180-300m. The Namibian Ministry of Mines and Energy of 2011 permitted two companies to harvest this bounty.

The Sandpiper phosphate mining project involving two Australian-based companies, Minemakers and Union Resources, with a Namibian partner, became a flashpoint of opposition from local and international environmental groups which eventually led to a moratorium on phosphate mining.

That ban is no longer officially in place but the Sandpiper project, now in the hands of a company called Namibian Marine Phosphate, remains just that: a project.

‘YES, IF’ AND FOUR TESTS

Environmental opposition remains the biggest obstacle to such projects getting off the ground and into the deep water, and much of this is rooted in the potential threat to life at the bottom of the sea.

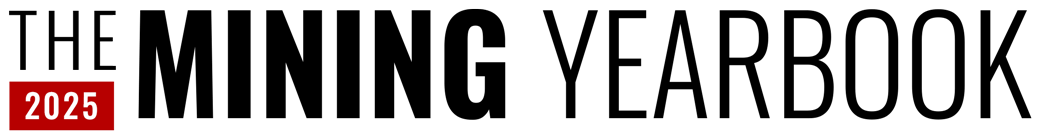

Once thought to be a dark and cold realm largely devoid of life, the deep sea is now regarded as the largest ecosystem on the planet, teeming with biodiversity and many species that have yet to be discovered and identified by science.

“The deep sea is the most extensive habitat on our planet, and it supports surprisingly high biodiversity,” says one peer-reviewed 2021 study in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

“It remains uncertain whether the deep sea is resilient toward anthropogenic disturbances, yet this is difficult to research on short timescales. There is little hope for areas in which exploitation, such as deep-sea mining, will be directly impacting the benthos [the community of organisms that live on or near the bottom of a body of water] and proper regulations are required to preserve biodiversity in the deep sea.”

So, does deep-sea mining have a future or is it a myth of the deep?

Rohitesh Dhawan, CEO of the London-based International Council on Mining and Metals, told Miningmx that in his view, a “Yes, If” approach was the best way forward.

“Most of the rich nodules lie in international waters that are not in any country’s 200-mile zone. That is governed by the International Seabed Authority and that will give you the guidebook on how to do that responsibly. That is where the issues lie because that rule book hasn’t yet been developed,” Dhawan said.

“There are questions around the ISA as a governance mechanism. And there are concerns that a country like the US may disregard and not care what the ISA says and allow companies to exploit those nodules in international waters” – which is precisely the fight that the Trump administration seems intent on provoking.

Dhawan went on to say that amid the polarising debates that surround the issue, it was best to take a deep breath before taking a deep dive. “I think a better way to think about this is a ‘yes, if’ type approach. Because what a yes, if approach does is to say ‘yes’, we should be able to get minerals wherever they’re found ‘if’ we have a series of tests that need to be proven before you do it,” he said.

Meanwhile, the need – and the resulting demand – for the riches at the bottom of the sea is only going to grow.

Mining on land is difficult enough

Paul Dunne, President, Minerals Council South Africa

Along those lines he sketched out four tests.

“So if number 1, you can demonstrate a clear baseline of what life currently exists and how that life responds to disturbance. Secondly, you can do this if there are mechanisms that have proven to be effective and mitigating on any impacts on those life forms. Third, you can do this if there is an accepted rulebook on how to do this responsibly. Fourth, you can do deep-sea mining if the governance of the process is seen as widely credible,” Dhawan said.

“And those are just four tests that I would be applying to determine if you can do it responsibly or not. And as things stand, I don’t think you can meet those four tests.”

Costs for now remain prohibitive and environmental concerns are not alarmist. But grappling with rapid climate change linked to fossil fuel usage has become one of the defining issues of this epoch, and doing this requires much of the resource wealth that lies in the deep sea.

Dhawan’s four tests may someday get a passing grade. Like the coelacanth, the ocean still has many mysteries, and some of them could hold the keys to the future of the mining industry, the global economy and even life on Earth.