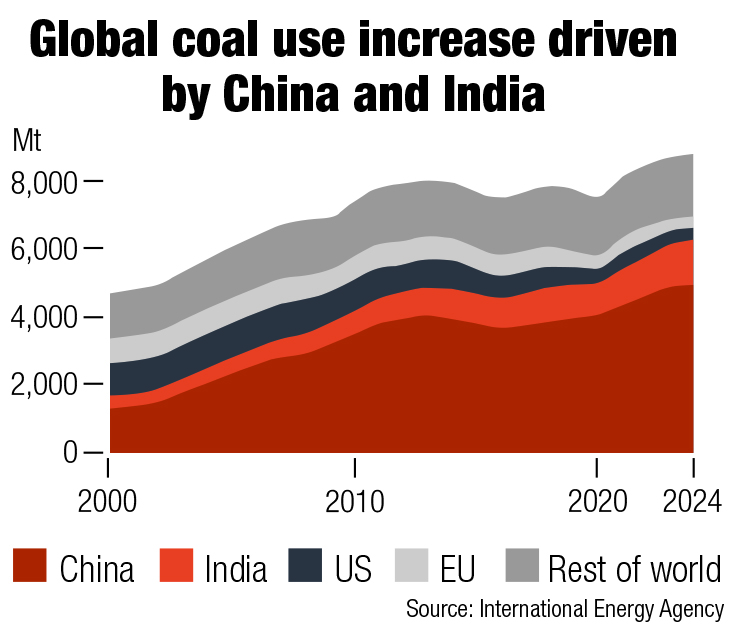

The world burns nearly double the amount of coal today compared to 2000, and four times the amount consumed in 1950. Every minute, 16,700 tons of coal are excavated globally – enough to fill seven Olympic swimming pools, according to the Financial Times in a report in July.

In fact, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has changed its mind on a previous forecast that coal demand peaked in 2013. Now it talks of a plateau rather than a peak. “We changed our wording,” Carlos Fernández Alvarez, head of gas, coal and power markets at the IEA, told the newspaper.

Don’t tell this to Vuslat Bayoğlu, MD of Menar, a 3.5-million-ton-a-year coal producer in Johannesburg. He’s been arguing with renewable energy advocates over the risks of poverty over climate change for years. One argument he makes is that for a country like SA, where the recent unemployment rate was 32.9%, the focus should be on producing cleaner coal rather than pressuring an entire industry to shut.

“I think there is still a massive resistance to coal,” says Bayoğlu. “If you go to a bank in SA, they will say they will not fund a coal-fired power station.” Despite this, the country doesn’t have the ability to fund the major capital investment required for gas or renewable power without providing massive security for foreign loans. “That means we’re going to give our future – our kids’ future – as security,” he says.

“The risk of poverty far overrides the environmental risk on this planet,” says Mark Bristow, CEO of Canadian firm Barrick Mining. He believes developing economies have not been supported, especially by the West. It’s a view shared by outgoing Thungela Resources CEO July Ndlovu. “An unmanaged decline in coal, driven by global politics but blind to local consequence, risks triggering economic and social dislocation on a massive scale,” he said in a recent article in BusinessLive.

He also rejected “false binaries” such as the argument of coal over renewables or climate versus development, or growth versus exit. These are oversimplifications of a far more complex challenge which is for an energy transition that is “honest, inclusive and disciplined”.

In other developing economies, coal power competes directly with renewables which, in the case of China – which consumes half the world’s coal – it has to. Despite renewable energy growth, China’s coal consumption may continue rising in absolute terms, says the IEA. India draws three-quarters of its electricity from coal despite significant renewable investments. The government expects domestic coal production to rise 6-7% annually, reaching 1.5 billion tons by 2030.

Citing its research, the Financial Times said there was a 97% probability that Chinese coal consumption in 2026 would exceed IEA forecasts, while commodity analyst Tom Price expected coal use to keep rising 0.5-1% annually.

While it’s probably not correct to say coal’s reputation has been rehabilitated, the COVID pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine by Russia both reminded developed nations of their economic and strategic vulnerability. “If we have a parallel world in which we remove COVID, and we remove Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I think the coal trajectory would have been very much as expected,” said Alvarez. As a result, Bayoğlu thinks there’s a logic for Europe and South Africa to mine and sell coal. “We can’t afford not to have coal power,” he says.