New draft legislation is being considered while SA faces international uncertainty and domestic upheavals as its government of national unity (GNU) is on shaky ground.

In May this year, South Africa’s cabinet approved the draft Mineral Resources Development Amendment Bill along with the country’s Critical Minerals and Metals Strategy, opening the draft legislation for public comment until 13 August.

Mineral and Petroleum Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe said the bill aims to provide greater policy and regulatory certainty, boost investor confidence, improve turnaround times for licensing and mining rights approvals, and cut red tape.

However, analysts, industry stakeholders and commentators argue that certain provisions in the bill may have the opposite effect. Two areas of particular concern are the empowerment provisions for black economic empowerment (BEE) and tighter state control over company transactions.

In a correction notice published early in June, Mantashe reversed the two provisions in the draft bill that sought to expand state control over the mining sector. These included the removal of the proposed BEE requirement for prospecting rights, as well as a clause that would have required ministerial consent for changes in control of listed companies.

Bowmans mining lawyers Charles Young and Wandisile Mandlana view Mantashe’s unusual correction of the two provisions in the middle of consultation as a step in the right direction, but caution that there are issues that remain unresolved.

The controversial proposal to apply empowerment ownership requirements to prospecting and exploration rights was not intended to be included in the draft bill. Says Mandlana: “The minister appeared surprised that empowerment requirements in respect of prospecting were in the draft bill. That said, one should give him credit for making that change.”

An area of concern that remains, however, is the definition and treatment of “change of control” (Section 11 of the draft bill), especially regarding listed companies. The original amendments required ministerial consent for any change in control of a company holding a mining right, including in listed entities where shares trade frequently on the open market.

What you see in this bill is effectively more of the same. It’s mostly stick, very little carrot

Peter Leon

The revised draft still includes references to “an interest” in unlisted companies, which could imply that any change in ownership – even indirect – would need ministerial approval.

The amendment also does not clarify the distinction between direct and indirect shareholding in law, leaving the issue unresolved. “We think the department missed an opportunity to clarify a section in the draft bill that was already complex and unclear,” says Young.

The amendment still allows for ministerial consent for minor corporate actions, such as share buybacks, employee share schemes, or changes in community trust structures, which could paralyse ordinary business operations.

Bowmans stresses that the bill needs further amendments to achieve its stated objective, namely to boost investor confidence.

Peter Leon, mining lawyer and director at Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer, noted at a webinar following the initial release of the draft bill that, given the unpredictability regarding the mining code in South Africa, one would have thought that the government would have used the opportunity to consider all policy issues around mining. “What you see in this bill is effectively more of the same. It’s mostly stick, very little carrot.”

Lili Nupen, mining lawyer and director at NSDV Law, remains optimistic that the department will eventually take industry and stakeholder input on board. “It’s important not to panic. The department is not out to negatively impact the mining industry. They are open to having discussions about what doesn’t work and why it doesn’t work. They want proposals as to what industry thinks could work.”

The Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) seems unconvinced. At the 2025 Junior Indaba in May, Mzila Mthenjane, CEO of the MCSA, expressed frustration that the council’s input had not been reflected in the new draft bill. He described the council’s prior engagements with the Department of Mineral and Petroleum Resources as “very high level” and noted that no access had been given to the underlying wording of the draft bill or how it was being amended.

Even after Mantashe’s reversal of two of the problematic provisions, the MCSA noted in a statement that the bill “in its current form” does not encourage or sustain the growth and investment that the industry needs to realise its potential.” The council declined to comment further, stressing that it would submit its input before the August deadline.

Even though BEE provisions for prospecting and exploration were removed from the draft bill, there are proposed amendments to the BEE framework for mining rights, aligning empowerment provisions with those outlined in the Broad-Based BEE (B-BBEE) Act of 2003.

It also makes compliance mandatory by requiring the minister to impose applicable BEE conditions when awarding mining rights. Furthermore, the bill gives the minister the authority to revise or withdraw existing BEE obligations for companies that already hold mining rights.

Political analyst Theo Venter says it is as if SA’s government is “tone-deaf” in its policymaking. “They can’t read the room. For example, there is less prospecting because there is no clear guarantee that if I discover a rare earth mineral, I’ll be allowed to mine it.” After all that, BEE requirements kick in.

Nupen says that when it comes to the empowerment-related amendments in the new draft bill, it is more critical for the mining industry to have clarity on what is required of them, rather than focusing solely on a fixed percentage of black ownership. “As long as they know what’s required, and that it won’t change overnight and that additional requirements won’t be added, because that is what is creating anxiety.”

EQUITY EQUIVALENCE

The recent talk of an equity equivalent programme as an alternative to black ownership for multinationals in the information and communications technology sector has sparked optimism that a similar approach could be considered for BEE compliance in the mining industry.

Currently, companies applying for an electronic communications network services licence are required to allocate 30% ownership of the business to historically disadvantaged groups.

South African-born billionaire Elon Musk’s satellite internet company, Starlink, may reportedly invest around R2bn in SA as part of a proposed alternative to meeting BEE requirements, according to Business Day. Rather than transferring equity to local partners, Starlink has purportedly committed to investing in infrastructure that would support the broader Southern African Development Community region.

This includes working with South African firms to build infrastructure, lease land and fibre, and provide energy, security, and maintenance services. The company is said to be aiming to finalise an agreement with South African authorities before the G20 summit takes place in Johannesburg in November.

Although Musk has expressed interest in launching Starlink services in his country of birth, he has previously refused to cede ownership in the company to meet BEE requirements.

In response, Communications and Digital Technologies Minister Solly Malatsi has suggested potential revisions to current BEE obligations for multinational satellite providers in the form of “equity equivalence”. The proposal would allow these companies to qualify for operating licences by investing in black-owned businesses and infrastructure in SA instead of being required to take on black shareholders.

However, Malatsi confirmed that the final decision to grant Starlink an operating licence will lie with SA’s telecommunications regulator, Icasa.

BEE specialist Paul Janisch says the proposal is a move in the right direction. “The government may deny this, but our employment and empowerment policies have proven to be a major deterrent to foreign-owned companies operating in SA.”

He points out that equity equivalence is costly. “An amount of money needs to be invested in these projects over a two- to 10-year period. To describe the investment values as costly would be an understatement. The investment can either be 25% of the value of the local entity, or 4% of total revenue each year.”

Bowmans’ Mandlana clarifies that equity equivalence was first introduced to mining via the 2018 Mining Charter and was coupled with beneficiation requirements. “However, it was caught up in the broader fight about the lawfulness of the Mining Charter and despite the complexities and costs associated with equity equivalence programmes, equity equivalence is still accepted to be an empowerment tool in mining.”

He notes that the empowerment regime envisaged under section 100(3)(b) and the regulations should provide for a clear framework for equity equivalence. “Such a framework should be published together with the draft bill, such that the industry comments on the empowerment framework for the minerals industry holistically.”

Bowmans’ Young adds that “flexibility” provided by equity equivalence programmes is good from an investor perspective. “Equity equivalence programmes, if done correctly, still essentially recognise benefits flowing to the country, but are more flexible in terms of the structure through which it is achieved.” He cautions, though, that real equity remains politically sensitive. “Real ownership in mining is prized, and I can’t see the country moving away from that entirely.”

Janisch stresses that it is “too early” to celebrate the “perceived” relaxation of SA’s empowerment regulations.

“The proof lies in how the government and regulators approach the application of equity equivalence,” he notes.

PRESIDENTIAL BLESSINGS

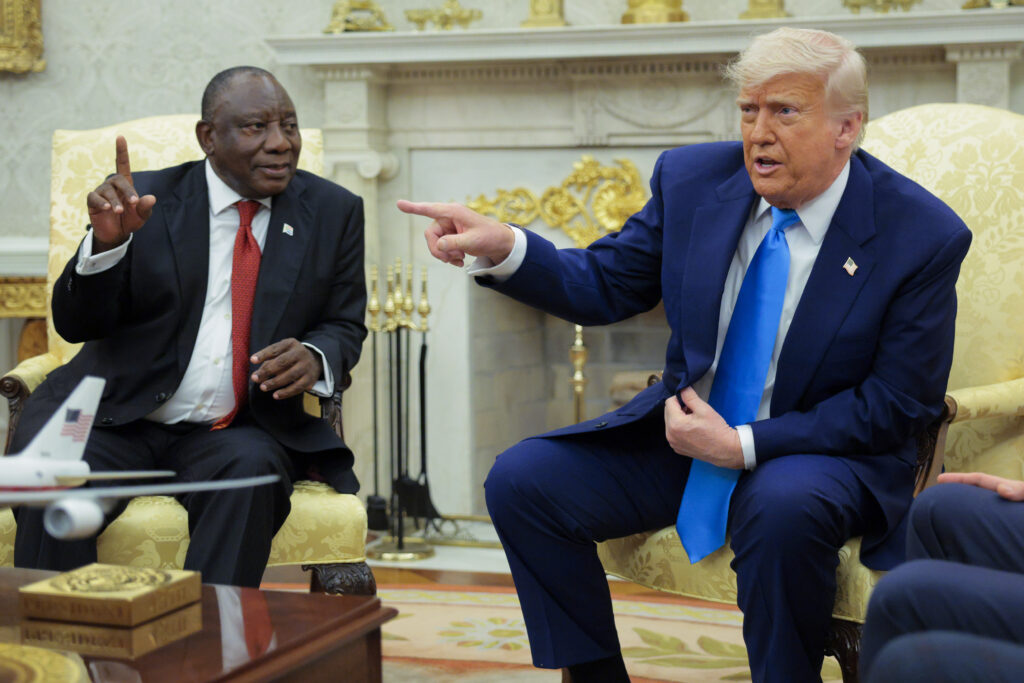

The concept has seemingly received the green light from President Cyril Ramaphosa himself.

In his newsletter in the first week of July, Ramaphosa wrote that equity equivalent programmes have proved to be a “practical B-BBEE compliance tool” for multinationals, citing deals with global giants, such as Hewlett-Packard, Samsung, JP Morgan, Amazon, and IBM and automotive firms such as BMW, Volkswagen, Nissan and Toyota in the past.

Ramaphosa was careful to stress that equity equivalence should not be viewed as a “circumvention” of B-BBEE legislation or as a concession tailored to the demands of any specific company or sector. His remarks appeared to be a veiled reference to Starlink, following reports that Ramaphosa had extended an offer to the company to operate in SA shortly before meeting President Donald Trump in the Oval Office in May.

“Firstly, [it] is not new and … is firmly embedded in our laws and is not an attempt to ‘water down’ B-BBEE,” he stated. The president emphasised that South Africa’s empowerment laws remain central to economic transformation and “are here to stay”.

Uncertainty around BEE requirements and the possible introduction of equity equivalence schemes comes at a time when South Africa’s trade relationship with the US is unpredictable, due in part to a shifting global trade landscape.

Since Trump’s re-election to a second term as US president, SA has found itself in the firing line as part of his renewed push for trade reciprocity and protection of US economic interests.

Trump has criticised countries that, in his view, benefit disproportionately from trade agreements with the US, and SA, as a beneficiary of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), is under increased scrutiny.

Fortunately for SA, the US has a growing interest in critical minerals – an area where the country is well positioned. Gold, platinum group metals (PGMs) as well as base metals like manganese, nickel and zinc, are exempt from US tariffs. Although the recent threat of a copper import duty should dispel any notion metals are likely to remain off the radar indefinitely.

Other concerns for SA are that the US dislikes its statism, the unclear empowerment laws, and its perceived hostility to foreign investment, all of which have raised red flags in Washington.

Venter says the problem in South Africa’s mining industry is not tariffs, but “BEE and poor government policy”. Ramaphosa’s recent visit to the US has not removed uncertainty regarding trade relations with the US. The trip was intended to enable diplomatic and economic engagement, yet it remains unclear whether any concrete progress was made in stipulating conditions for a long-term trade deal.

Frans Cronje, economic and political analyst, views Ramaphosa’s visit as “a missed opportunity at a scale that is hard to comprehend”. He claimed that it is “a complete falsehood” to brand the discussions between Ramaphosa and Trump as successful. “It wasn’t. When you go to the Oval Office, you say: ‘We are here to offer you a deal. Here are the hard ideas’.”

Nevertheless, he believes there is goodwill from the US. “I would say the new US administration probably offers the best opportunity for SA’s young democracy to get out of the growth rut. Although we’re not rushing towards seizing the opportunity, it remains wide open.” This was before the US announced plans to slap a 30% tariff on the country’s exports, as well as those of a host of other developing economies.

REVISIONS TO FRAMEWORK DEAL

This emerged during a bilateral meeting on 24 June between SA’s trade ministry and a US trade representative held on the sidelines of the US-Africa Summit in Luanda, Angola.

They can’t read the room. There is less prospecting because there is no clear guarantee that if I discover a rare earth mineral, I’ll be allowed to mine it

Theo Venter

SA’s initial framework proposal, in which tariff exemptions for key exports like vehicles, steel, and aluminium were sought, also outlined increased cooperation on liquid natural gas, a joint critical minerals fund, and enhanced bilateral investment.

The country’s trade ministry has agreed to consider the US’s proposed new template for trade negotiations. It has also formally asked the US to extend its 9 July deadline for imposing increased tariffs to avoid a 31% duty on its exports. The request comes as several African countries seek more time to adjust to the new framework.

Venter suggests that behind the scenes, strategic groundwork is being laid for a deal with the US, particularly focused on gas and rare earth minerals. He says US companies are keen to help build or finance processing plants in SA to reduce Africa’s dependence on China. Cronje is of the view that South Africa’s position around the Cape Sea Route is of strategic importance. “We can leverage that.”

The US has a strategic interest in Southern Africa, he adds. “Sensible people say you can’t leave a backdoor into Southern Africa open. You’ll pay the price for that.”

His wish is that a “vast new bilateral investment treaty” will eventually emerge. “A new trans-Atlantic partnership. This is the scale on which we must think,” Cronje notes.

GNU: REFORM OR GRIDLOCK

Amid South Africa’s unsteady relations with the US, the country is navigating a complex domestic political landscape with the GNU, which emerged after the general elections in May 2024.

After the ANC’s support dropped to 40% in 2024, the ruling party offered all represented parties in Parliament an opportunity to join the GNU. Altogether, 11 parties are in the GNU, although the “marriage of convenience” – especially between the ANC and the official opposition, the DA – has turned into a “flirtation” with divorce, Louw Nel, senior political analyst at Oxford Economics, writes in a research note.

“The GNU’s primary success has been avoiding collapse – sometimes by the skin of its teeth,” Louw adds.

SA submitted a proposed framework deal with the US ahead of Ramaphosa’s visit, but the deal will most likely have to be revised after Washington’s proposed “standardised trade engagement template” for Sub-Saharan Africa.

Cronje says it would have been “wonderful” if the GNU could ignite 5% [economic] growth. “It would have been the case had it been led by more inspiring people. But to be realistic, one should think of what is happening in the GNU as the beginning of possible progress.”

Venter believes, based on proportional representation in the unity government, that the DA should have had more ministers in the GNU cabinet. “But the ANC did not want anyone else involved in state finances and key portfolios such as defence, foreign affairs and mining were monopolised.”

Venter however regards the 2025 Budget fallout as the “turning point” in the ANC’s “monopolisation” of policy.

“The DA has realised its power lies in Parliament, not in Cabinet. In the first four months of this year, they started using that power.”

Even though the DA does not have particular sway in key economic portfolios, Venter says political and policy changes happen in small steps, “not through sweeping moves. Over the next year or two, we’re going to see several areas where GNU members will use parliamentary action [to bring about change].”

“If we want to put the mining industry on a better political footing, the same process must unfold as with the budget and foreign policy. There must be a resistance to policy at the parliamentary level,” Venter says.